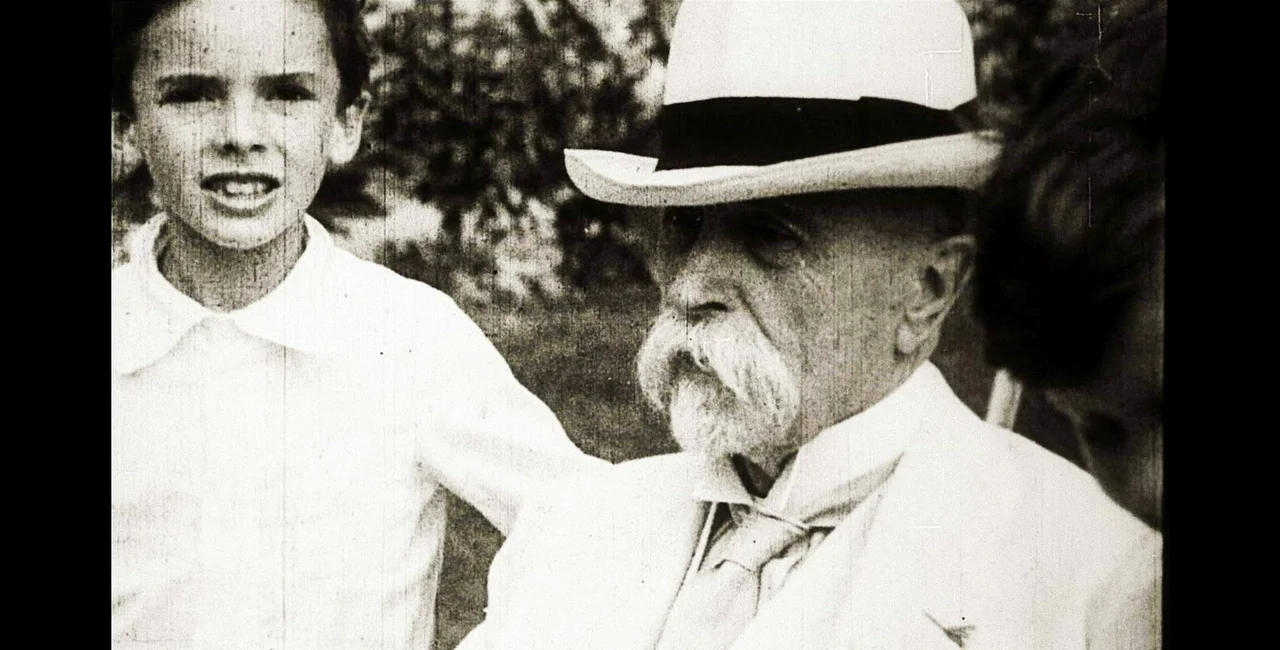

The final words of Czechoslovakia’s first president, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, are set to be unsealed Friday at Lány Castle, potentially offering a rare glimpse into the private life of one of Czechia’s most revered leaders.

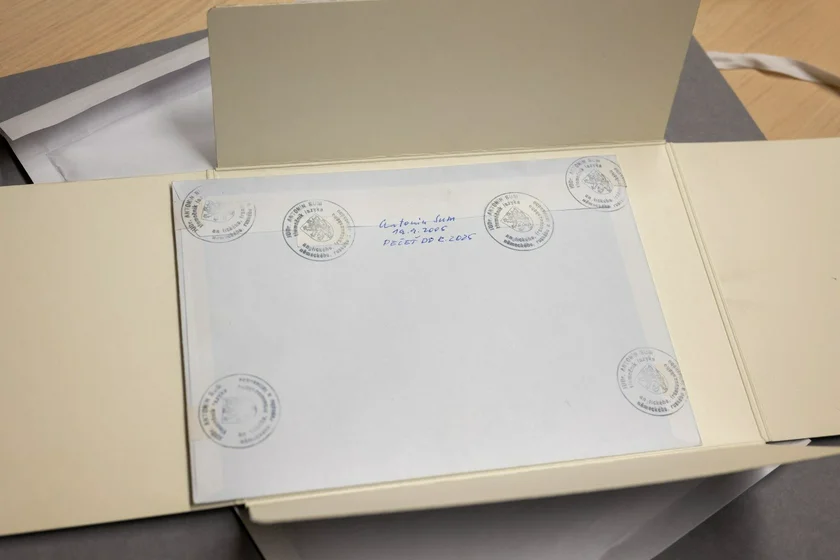

The envelope, preserved by the National Archives for 20 years, will be opened in the presence of President Petr Pavel, Masaryk’s great-granddaughter Charlotta Kotíková, and representatives of the Masaryk Institute.

The outcome of tomorrow’s reveal may be of particular interest to bilingual families living in the country today. Historians have predicted the text could be written in English, the language the statesman used at home with his American-born wife, Charlotte Garrigue, and their children.

“Masaryk had stroke attacks in 1934 and 1935, and at times the language he spoke with his family returned to him,” said Jiří Křesťan, historian and archivist at the Masaryk Institute.

In bilingual households, alternating between languages depending on context, audience, or emotion is known as code-switching. Masaryk’s English resurfacing more than a decade after his wife’s death in 1923 offers a striking example of how it works: language is stored not just as vocabulary, but as networks tied to family, emotion, and identity that the brain can access under stress.

Research from the National Health Institute shows that bilinguals often code-switch during emotional moments, using a native language to express intensity and a second language to temper it. For Masaryk, English may have allowed him to navigate moments of vulnerability, instinctively reaching for the language of love and family.

Křesťan notes the existence of a similar message that Masaryk dictated to son Jan Masaryk in the presence of Edvard Beneš three years before his death. "The English language prevails there,” he says.

The envelope, handed to the National Archives in 2005 by Jan Masaryk’s personal secretary Antonín Sum, is believed to contain words the former president, who governed the Czechoslovak Republic from 1918 to 1935, dictated to his son shortly before his death in September 1937.

Its contents remain a mystery, with speculation ranging from personal messages to reflections on society. Historian Dagmar Hájková will attempt to decipher the letter despite the likely hurried handwriting and time-worn paper, as Czechs hope for further glimpse into the personal reflections of a man often seen as the father of the nation.

For bilingual families, Masaryk’s choice of English at the moment of death could prove to be a poetic reveal, resonating with anyone who has instinctively reverted to their native (or non-native) tongue to communicate with those closest to them.

And in today’s politically fractured climate, the fact that the nation’s first—and arguably greatest—president may have left a message in a second language reminds us that the country he helped build was designed for inclusion. As Masaryk himself said, “The more languages you know, the more you are human.”